One Health biosecurity in action

Published on 25/05/2021

View this page in:

VietnameseThe concept of One Health is not new, and the linkage between environment and human health was recognised thousands of years ago. Biosecurity is fundamentally a One Health issue. At its core, biosecurity is about managing risk.

We know that some animal diseases can have direct and indirect human health consequences – for example, with zoonotic diseases like some influenza viruses; as well as by impacting food sources and security, and prosperity. We also know that some animal disease events can have significant impacts on the economy and prosperity, including through productivity losses and trade impacts.

We also need to go beyond considering consequences to animal and human health, welfare and prosperity, to the direct and indirect impacts animal health can have on the environment. And conversely, we cannot forget the direct and indirect impacts of human and environmental health issues, on animal health and welfare.

Emerging risks

By adopting a One Health approach, biosecurity risk can most effectively and comprehensively be assessed and managed.

In addition to seeking to minimise harm, I think it is also important to note that good biosecurity confers positive value – improving health and welfare, increasing productivity, supporting food security and enhancing prosperity.

Managing threats and optimising health will only become more important. We are living and working in a world which is under increasing pressure and where biosecurity risks are constantly evolving and emerging – driven largely by human behaviour. As these threats continue to escalate in both scale and frequency, the urgency of adopting One Health approaches, to at least keep pace, is only becoming more critical.

While the COVID-19 pandemic, and its devastating impacts, may have propelled One Health into mainstream media and the front of more people’s minds, implementation is unfortunately often still lacking.

Without genuine One Health activities to effectively understand and address animal, human and environmental health threats, we risk being overwhelmed trying to manage continual or even concurrent emergencies, rather than preventing or being able to respond to new threats.

This is where good governance also comes in. Biosecurity is a legal issue, for good reason, and must be underpinned by robust governance including legislation and policies. One Health approaches similarly need to be embedded in effective governance arrangements to effect long lasting change.

International governance is necessary to embed this approach and ensure changes in policy and legislation for these global threats. Intergovernmental agencies play a crucial role in providing leadership and modelling One Health collaboration at the highest level for these threats that not only do not respect sectors, but do not respect borders.

Shared responsibility

In Australia our biosecurity system is built on the concept of ‘shared responsibility’. That is, all system participants, including governments, the private sector and the public, are partners and have an important part to play. This is underpinned by legislation and regulatory systems; a strong risk analysis system; controls across the biosecurity continuum – including pre-border, at the border, and post-border; compliance and enforcement activities; national emergency preparedness, response, and recovery arrangements; and system performance reviews amongst other things.

There are formal and informal mechanisms that support One Health collaborations at a number of levels, including an agriculture member participating in the human-health Communicable Disease Network Australia and various veterinary-human health collaborations. Along with my role and that of the Australian Chief Plant Protection Officer, there is now an Australian Chief Environmental Biosecurity Officer. There is strong collaboration between us – and with the Australian Government Chief Medical Officer.

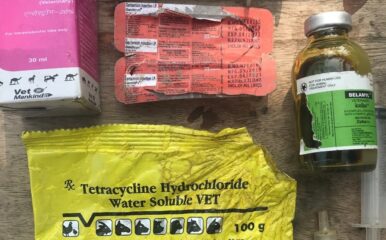

Antimicrobial resistance

One example of where One Health governance has been implemented to improve human and animal health is the tackling of increased antimicrobial resistance (AMR) globally. The Australian government provides technical input towards international fora discussions and assessments involving AMR.

Nationally, we continue to focus on AMR as a priority. In March 2020, the Australian government endorsed Australia’s National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy – 2020 and Beyond, setting a 20 year vision to protect the health of people, animals and the environment against AMR. Since February 2021, we have a One Health Master Action Plan (OHMAP) to support the implementation of the national AMR strategy.

To ensure ongoing commitment to the strategy, we also have developed a governance framework comprising the Antimicrobial Resistance Governance Group and the Australian Strategy and Technical Advisory Group on AMR, which drive the overall direction, priorities and implementation approaches to support the national AMR strategy.

Locally, there are a number of initiatives being undertaken, in particular the development and use of prescribing guidelines – the poultry prescribing guideline was released in September 2020, veterinary stewardship training through the AMR Vet Collective website, and public engagement.

Underpinning all this work is biosecurity.

Biosecurity is an essential component to reducing and preventing the burden of animal disease on farms and in clinics, and thus the requirement for treatment such as with antimicrobials.

Overall, when all essential system components are implemented, then the low impact and risk of AMR is maintained. Ensuring the sustainable and judicious use of antibiotics in human and animal medicine is critical to mitigating AMR.

The challenges we face are immense: AMR, pandemics, food insecurity, environmental emergencies and issues that are yet to emerge. The only solution is one that brings together all relevant sectors and disciplines – including health and environment professionals, sociologists and economists – in a One Health framework.

Biosecurity at the farm or vet clinic and at the national level is a critical contributor, and that is why the development of standards through the intergovernmental bodies such as the OIE and Codex are so important. They not only support trade, but they underpin and support enhanced biosecurity, and all the benefits this confers. We must keep the momentum going – we all depend on it.

Dr Mark Schipp is the Australian Chief Veterinary Officer.

View Dr Mark Schipp and UK Chief veterinary Officer Professor Christine Middlemiss in our Roadmap Series event ‘One Health: biosecurity governance’.

View Dr Mark Schipp and UK Chief veterinary Officer Professor Christine Middlemiss in our Roadmap Series event ‘One Health: biosecurity governance’.