How lockdown offered an unexpected opportunity to broaden researcher and stakeholder engagement

Published on 28/03/2023

Mat Hennessey

View this page in:

VietnameseThe recent publication of a One Health paper offered an opportunity to reflect on how collaborations between multidisciplinary teams based in different countries work in reality.

Reaching out to diverse stakeholders and co-opting them in designing stewardship interventions was the central goal of our project, the One Health Antibiotic Stewardship in Society (OASIS) project. The project began with formative research to understand how antibiotics are distributed to rural communities in West Bengal so that it could use this evidence to identify, together with key stakeholders, ways of developing antibiotic stewardship interventions for both people and livestock. As with the One Health Poultry Hub, OASIS took a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach to using research to co-design interventions with research participants.

Our project was a collaboration between several institutions, in the UK and in India, and brought together researchers from veterinary public health, animal health, agricultural economics, social science, microbiology and human medicine. This multidisciplinary team contributed to the research design, data collection and analysis, and writing up and dissemination of the research findings.

Fortunately, fieldwork activities for our project took place just before the global COVID-19 pandemic, and UK-based researchers were able to travel to West Bengal to work with the local researchers to plan our data collection activities. These consisted of interviews with people involved in antibiotic distribution, including pharmaceutical companies, retailers and health care providers, as well as members of local communities who would be using antibiotics, including livestock-producing households.

Antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic use and resistance is a key example of a One Health problem. Antibiotics are used globally to treat and prevent infections in both human and animal populations and can lead to the undesirable result of antibiotic resistance where bacteria are able to survive antibiotic treatment.

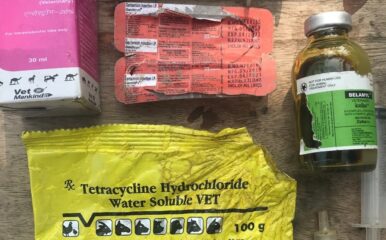

Within our project we were particularly interested in identifying and understanding crossover use of antibiotics, i.e., where human antibiotics were used in animals and where animal antibiotics were used in people. The project used value chain analysis, an economic approach, to understand the distribution of antibiotics and the power dynamics within the system which affect antibiotic governance.

We were in the data analysis stages of our work when the COVID-19 pandemic hit and plans for our in-person stakeholder meeting had to adapt. These meetings had been intended as an ideal opportunity to share initial findings with those people with a vested interest in the system we were studying and doing this face-to-face would have provided opportunity for deeper discussions to workshop ideas.

These meetings, and subsequent stakeholder meetings, had to be held online – and the strategy worked so well, both for us and for the stakeholders, that we continued to meet virtually even after lockdown restrictions were lifted. The project team held extensive virtual consultations with stakeholders within the health system, including medical practitioners, policymakers, pharmaceutical industry leaders, health and regulatory departments, academics and researchers and health workers in the human and veterinary sector.

To make these meetings interactive, we used digital whiteboard software and breakout rooms to collect inputs from stakeholders before using an online voting system to vote for the best options. Being online meant we were able to include those stakeholders who may not have been able to travel to a physical meeting.

Online benefits

We also adapted our work at the start of the pandemic and conducted an online COVID-19 impact survey where we were able to reach more than 1,000 formal and informal human health care providers across six Indian states to ask about changes to antibiotic usage over the pandemic.

Similarly, the research team involved in the project now met regularly online, something we were not doing as much before the pandemic. This allowed all those involved in the project – from different disciplines, institutions and countries – to provide their input and voice to the ongoing data analysis.

Some of our research findings – published in ‘Pharma-cartography: Navigating the complexities of antibiotic supply to livestock in West Bengal, India’ and also in ‘If it works in people, why not animals?’ – demonstrated that livestock health care providers in the study sites engaged in crossover use of human antibiotics in livestock, though veterinary antibiotics were not used for human health due to their perceived side effects.

Both the veterinary and human health care sectors were being used to provide antibiotics to livestock, frequently through informal routes, i.e., outside of the legislation designed to control antibiotic use. Examples of these informal routes included obtaining antibiotics without a prescription from human and veterinary drug stores, buying antibiotics for animals from human health care providers and buying antibiotics from poultry shops (a shop where people bought chicks, feed, and medicines needed for production).

Antibiotic stewardship

Another key finding was that many antibiotic providers, especially the informal ones in the animal health care sector, lacked awareness of and access to antibiotic stewardship guidelines.

Consequently, researchers in our group have been working with stakeholders to produce guidelines for key livestock diseases. It is hoped that these locally relevant guidelines will be made available to all antibiotic prescribers to promote good antibiotic practices. Provisional drafts of guidelines for five common diseases seen at the primary care level were subsequently developed through an expert committee and are being field tested.

The pandemic pushed many of our social interactions online, forcing us to embrace technologies we had previously avoided. Now, as we go back to a ‘new’ normal, it may be useful to think about how we integrate online tech into our research projects to maximise engagement – both with research teams and those we seek to research.

- OASIS project members Indranil Samanta, Priya Balasubramaniam, Anagha Pradeep, John-Christophe Arnold and Meenakshi Gautham also contributed to this blog.