Food equity: addressing the social, economic and political barriers

Published on 16/10/2022

Nguyen Minh Khue/VNUA

For those of us living in Europe, 2022 might feel like a year where people and governments are increasingly worried about poverty and food insecurity. Just as we were grappling with the long-term social and economic implications of the global pandemic, the war in Ukraine arrived, which has highlighted the interconnectedness of energy and food prices. As a result, an increasing number of families are wondering how they will put food on the table in the coming months. Also, news from around the world – including Ethiopia and Yemen – is filled with disturbing accounts of poverty, famine and food insecurity caused by international trade, climate-related disasters and conflicts.

What is clear from all these crises, either here in Europe or elsewhere, is that those who suffer are socially and economically marginalised even before the crises have unfolded. This means that to tackle these immediate and pertinent issues, we actually need to look deeper into our social, economic and political structures that keep vulnerable people poor and marginalised.

Vulnerability to health and economic risks

Through the One Health Poultry Hub, we have been exploring such structural dynamics that lead to some groups of people becoming further vulnerable to economic and health risks arising from poultry production, trade and consumption. For example, many people across the world, including in the Asian countries where we work, earn their living from jobs related to raising, trading and processing animals. But how they earn their living and whether their salaries and profits are distributed equally depends on the wider and deeper structures imposed by our social, economic and political environments. Small-scale animal farms, for example, operate in a precarious environment where access to loans and land is limited.

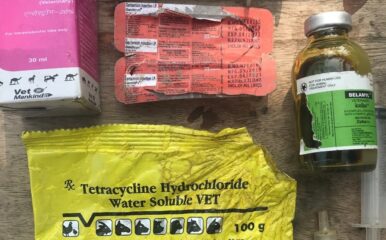

As a result, they rely on informal credit providers who charge a very high interest rate to borrow money to invest in their farms and animals’ health, putting pressure on household finances. The lack of access to formal credit also facilitates farmers being locked into a potentially exploitative relationship with traders who provide them with credit. This intricate socio-economic power imbalance has implications on the ways in which farmers invest in controlling chicken diseases, and therefore their occupational health and food safety along the poultry supply chain.

Vulnerability to health and economic risks experienced by some people is often because of our societal and political structures. And these structures are deeply influenced by how we think about our food systems and how we want them to look like in the future.

Gender norms and other forms of vulnerability

On my recent trip to Vietnam, we explored how gender norms and relations have implications on the different tasks performed by men and women. We also looked into how these influence people’s ability to earn a decent living from poultry-related businesses and reduce occupational health risks from zoonotic hazards. In Vietnam, generally speaking, men and women participate in the workforce equally. However, women are also expected to carry out the housework, including preparing meals and tidying up the house, as well as taking care of their family members – including the in-laws. Gender norms and perceived women’s ‘place in society’ are a strong indicator of how women participate in poultry-related businesses and their exposure to zoonotic hazards.

Beyond gender, many other forms of vulnerability exist in our societies. I had the chance to visit industrial slaughterhouses on the same trip. Many of the hired workers are migrant people from rural provinces looking for employment in the capital city, Hanoi. They are engaged in strenuous and stigmatised work – slaughtering animals throughout the night in a factory. Almost everyone we encountered was a migrant. Our work in the Covid Collective, with Vietnam National University of Agriculture, found that migrant workers experienced severe food insecurity during the pandemic. This was due to the legal structures that prevented them from taking advantage of the benefits and social safety nets provided by the government.

Leave no one behind

The government in Vietnam has been trying to modernise and industrialise animal slaughter and retail facilities, and move away from live chicken slaughter at markets and small-scale slaughter facilities. These processing and retail outlets are perceived to lack adequate hygiene and increase the risk of food poisoning. A series of policies has been implemented over the last decade to improve public health, environmental impact and food safety, but not much has changed.

I wonder what the future of the poultry sector in Vietnam will look like. Industrialisation and modernisation of the sector can improve food safety and veterinary public health. But the evidence is at best shaky and contested where industrialised facilities pose different kinds of risks than traditional supply chains. At the same time, the government’s ambition to modernise Vietnam’s animal sector has a huge implication on the livelihoods of people working in chicken production, processing and trade.

If Vietnam continues to rely on migrant people – who tend to come from disadvantaged mountainous areas and/or ethnic minority backgrounds – it also needs policies to reduce their vulnerability. These policies need to ensure that their workplaces are safe and without social stigma, and their jobs in the poultry – and other – sectors provide them with a decent income.

World Food Day is all about “leaving no one behind”. But to leave no one behind, we need more systematic thinking to tackle underlying structures in our societies, such as public policies that might have institutionalised certain social, cultural and historical prejudice.