We must rethink our food systems now to prevent the next pandemic

Published on 11/03/2021

Tmaximumge/pxhere

View this page in:

VietnameseIt all started at the beginning of 2020. I vividly remember the first reports. As an epidemiologist who has long worked in the field of zoonoses, I was asked for my opinion.

I said I felt the reported absence of human-to-human transmission meant we did not have to worry about this new virus.

As we now know, by the middle of January it became clear that this new virus did transmit among humans – and then everything changed rapidly.

Whatever we wish to speculate about the source of the virus and the apparent errors made during the initial response in China, the highly effective Chinese response by the latter part of January did significantly reduce the spread across China, as well as to other countries. Without this, a global tragedy would have occurred much sooner. The speedy Chinese response allowed other countries at least a little more time to get prepared in terms of control policies and vaccine development.

It has been impressive too to see how the global scientific community has responded to the challenge of SARS CoV2, in terms of generating data about the infection and its diagnosis and clinical progression, its epidemiology and the impact of different interventions, including vaccine development.

International coordination, via the World Health Organization (WHO) has also been important, with WHO having had a key role in facilitating the information flow.

One Health

However, after a series of widely noted zoonotic disease outbreaks over the last 30 years, including avian flu outbreaks in 1997, SARS in 2003, swine flu in 2009, Ebola in 2013-16 and Zika in 2015-16, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic also highlighted some failures.

Notably, it confirmed yet again the need to adopt an interdisciplinary approach if we really are serious about significantly reducing the risk of future pandemic zoonoses.

The One Health concept provides a platform for a more effective approach to science and to policy development that is now widely known and politically accepted. But only small advances have been made in its adoption, and these have only happened in a relatively small number of countries.

They were then not sufficient for these countries, let alone the global community, to deal more effectively with the tsunami-like effect of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Perhaps we should not be surprised. We know it is not easy to bring about big changes in institutions when the ‘only’ incentive is the prevention of a disease outbreak that may happen – or not.

We can only hope that the pandemic has provided sufficient evidence to the global community for the need to adopt true One Health risk governance with a degree of urgency, and that this also needs to have a functional global dimension.

My fear though is that we will all be so mentally exhausted once the pandemic has been brought under control, hopefully in 2022, that there will be limited political appetite for more changes. That could have consequences that are even more tragic than those we have already seen with SARS CoV2.

Livestock production

An important component of One Health risk governance – and one that no amount of post-pandemic exhaustion must get in the way of – will be a review of our national and global food systems.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a platform and metrics that can and should be used in that process. It has been utterly disappointing that the global community has failed to create more awareness about the importance of the SDGs and that policymakers have failed to commonly benchmark their policy decisions against them. But that can change.

With food systems, we need to reflect on the role of livestock production.

Major changes are needed as part of measures to prevent the next pandemic. It is a mistake to simplistically focus on the early detection of new pathogens in wild animal reservoirs, together with the management of the interface between these, humans and domestic animals.

Pathogens are a natural part of the ecosystem, and they cannot be eliminated. That means we need to live with them, which is exactly what people have always done.

What has changed of late, is that we humans have created environments where pathogens can spread more rapidly within particular species by increasing both species density and the opportunities for direct and indirect contact within and between species. This applies to humans living in megacities as much as to highly intensive livestock production.

The food systems that facilitate pathogen spread are complex, widespread and take many forms. For example, where there is high demand for meat in an urban centre, meat production is likely to intensify very rapidly within the vicinity of that centre but also further away if transport networks are adequate. And if it is a megacity, the increase in meat production in the food catchment area can be enormous, involving a mix of small, medium, large and very large farms, with often poor biosecurity, connected to consumers via a complex network of transporters, traders, butchers, retailers and more.

Naturally, infectious pathogens, including zoonotic ones, will spread very effectively in such a system. This has been demonstrated with the various avian flu epidemics.

There should be no doubt that these meat production systems need to change – and not just because of the zoonotic disease emergence risk but also because of the direct and indirect major adverse impact on the environment these systems bring with them, as well as poor animal welfare.

Equitable change

What needs to be realised is that the intensification of livestock systems is ultimately driven by mostly urban consumers’ ever-increasing demand for meat. We need to urgently consider how we can reverse that trend – and, importantly, do that in an equitable fashion.

High-income countries or consumers must not be left to define the criteria to their own benefit.

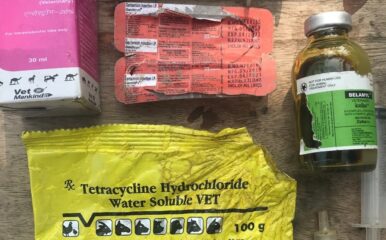

In addition, there cannot be any doubt that the way we produce meat needs to change, and most likely change dramatically. This is about thinking about the livestock husbandry conditions and animal welfare standards we require, how we manage livestock disease, how meat is processed and marketed and even how it is consumed.

The One Health Poultry Hub aims to tackle all these issues in the case of chicken production, researching in four Asian countries that are all very different from eco-social perspectives. The objective of our research is to inform safer, more sustainable chicken and egg production.

On the first anniversary of the declaration of a pandemic – and with ongoing avian influenza outbreaks worldwide – we are proud to be able to make an essential contribution to pandemic-preventing research.