Why gender is key for the future of chicken meat and eggs

Published on 18/01/2021

M. Yousuf Tushar/ WorldFish CC BY 2.0

Poultry include a wide range of birds, from indigenous to commercial breeds of chickens, from Muscovy to mallard ducks, and turkeys, guinea fowls, geese, quails, pigeons, ostriches, and pheasants. They are raised throughout the world, but the distribution of the different species and breeds varies across and within regions according to factors such as management and input requirements, market demand and price, and socio-cultural aspects.

Some species have been intensively genetically improved by humans and this has led to the development of a very specialised commercial sector. Here, the choice of bird species and breed can vary according to many factors such as ease of management, low requirements for external inputs, market demand and price, as well as the bird’s ability to withstand predators and diseases.

Family poultry

The term ‘family poultry’ is used to describe the full variety of small-scale poultry production systems found in developing countries. Rather than describing the production system per se, the term refers to the raising of poultry by individual households for food security and income.

Family poultry production contributes significantly to household food security, to poverty alleviation and to women’s self-reliance, with poultry and poultry products providing animal protein and micronutrients to the daily diets of farming families. Levels of production and productivity vary within and across productions systems, being influenced by many social, economic and market-related factors. The importance of poultry though cannot be overstated.

From development and environmental standpoints, village poultry production ‘backyard poultry’, practised by 60-80% of rural households in most rural and peri-urban areas of developing countries, is a valuable asset to the local population. For some poor households, poultry is often the only asset they can afford and is the main source of proteins for the family. Poultry can also be translated into regular small cash incomes with low transaction costs, and they can be used for entertaining guests and festivities.

Commercial poultry in intensive systems also make important contributions to growth and economic returns.

A women’s domain

Poultry have been raised by people for thousands of years in most rural societies in all regions of the world. Backyard poultry is kept with minimal inputs of resources, as birds scavenge to find feed. They are considered a very important contributor to smallholders’ livelihoods, and the most favourable for rural women.

In general, women are most active in the day-to-day management of family poultry in extensive systems, often with assistance from their children, while men occasionally contribute their time, for example in the purchase of inputs. In Kenya, the role of women is very dominant in animal husbandry activities, except in the area of cage repair which is done by men. In intensive poultry raising here, women still play an active role, especially in feeding, collecting eggs and handling heating for day-old chicks.

In Indonesia, which has an agriculture-based economy, the majority of households raise poultry. By participating in the entire operation, from feeding and management to marketing, women face problems balancing farming activities and taking care of the family and other social endeavours.

Gender roles depend on regional context. However, as the level of intensification of poultry production rises, the involvement and decision-making of women generally declines, with men taking over the economic decision-making over resources and benefits.

Opportunities and limitations

The growing demand for animal-source foods (ASF) has led to a livestock revolution privileging intensive poultry production, with much greater attention from policymakers and the private sector, investments, technologies, services and market access being geared towards mass poultry meat production.

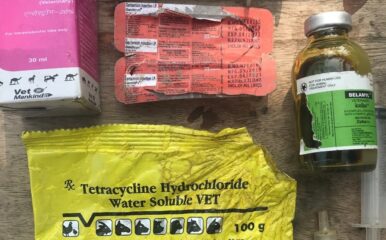

Consequently, smallholder poultry producers are facing unprecedented competition as they struggle with reduced access to markets, inputs and animal health programmes. Their flocks often suffer from recurring outbreaks of Newcastle disease, and are constrained by nutritional deficiency, the internal parasitic disease coccidiosis and more. The surge of avian influenza viruses, that pop up in different variants from time to time, as well as the COVID-19 crisis, have amplified the productivity burden of backyard poultry systems.

However, despite the fear of being left out, or marginalised, there may be opportunities for smallholders to benefit from the surge in ASF demand and in technologies.

Transitioning to sustainability

In the face of emerging infectious diseases, pests and climate change, we need to be more than cautious with regard to our natural resources, biodiversity and agro-ecosystems. An emphasis needs to be put on ensuring that poultry are healthy and do not pose risks to humans and the environment.

In this complex context, a One Health approach is more than ever of importance to ensure that livestock activities are sustainable and in harmony with the environment through increased biosecurity and a reduction of antimicrobial use and environmental impacts, among other factors.

A shift of mindset, policies, and investments has to happen, for governments to support smallholder poultry systems, including through continued access to training and awareness programmes. Context-specific and participatory approaches such as farmer field schools can play a key role in strengthening poultry producers’ knowledge and skills for holistic and sustainable agro-ecosystem management.

In particular, emphasis must be placed on women’s empowerment and gender equity so women can drive change and pass on knowledge to future generations.

Dr Clarisse Ingabire is a livestock specialist at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. She will be speaking in our next Roadmap Series event on Poultry production: the gender dimension on Wednesday 20th January.