Revitalising action against antimicrobial resistance at the state level in India

Published on 07/04/2022

Marcel Crozet/ILO via Flickr

In India, health is a state subject; thus, it is the state that is most key for determining ways forward to tackle AMR. Most of the areas affected by AMR fall in the state list in the Indian constitution, including human health, animal health, agriculture, and water and sanitation.

As such, the Colloquium on State Action Plans on Antimicrobial Resistance was an important meeting for One Health Poultry Hub researchers in India. AMR is a key focus of our One Health research – and the colloquium was crucial for understanding and identifying the pathways through which the Hub can contribute to ongoing debates, research and priority-setting regarding policy at the national and sub-national levels in India.

It was attended by community medicine and infectious disease experts, WHO representatives, AMR researchers and community members. Also, senior officials from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), activists, members of civil society organisations – and even individuals who had survived AMR. It was organised in New Delhi by ReAct Asia Pacific, World Animal Protection India and the World Health Organization (WHO) Country Office for India.

Poultry Hub co-Investigator Professor Rajib Dasgupta moderated a panel on ‘Behavioural change and local action plans on AMR’ and led discussions on community engagement and AMR. I attended as an observer.

Before the meeting, a communique had been prepared to revitalise the efforts made by states to draft State Action Plans for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance (SAPCAR) and to strengthen advocacy for AMR. Professor Dasgupta contributed to this draft, which was discussed and revised, with contributions from the multiple stakeholders present.

India and AMR

Action against AMR in India has been a little slow, despite being acknowledged as one of the biggest public health concerns by the global health community since the early 2000s. The WHO first declared AMR a grave threat in 2001, but little progress was made in India until 2011 when the country first developed a policy for its containment. However, this lacked a holistic approach, with an inadequate focus on the environment, the food chain and animal health.

WHO member states endorsed the Global Action Plan on AMR in 2016, and this was firmly supported by the then Indian Health Minister at the World Health Assembly. A National Action Plan was drafted in 2017 with support from the WHO Country Office, and this marked India’s first political commitment to address AMR through multisectoral collaboration.

The action plan had six pillars and 16 focus areas, including awareness and understanding, knowledge and evidence, infection prevention and control, optimising usage through better regulation, research and innovation, and collaboration and funding. India now also has a national guideline for infection prevention and control that was developed in partnership with the MoHFW and the National Centre for Disease Control.

In addition, India has bilateral ties with seven countries for co-learning on AMR, data sharing, surveillance and diagnostics etc.

In 2019, the MoHFW drafted a guidance document to help states develop their AMR action plans. This drew greatly on the experience of the state of Kerala, the first state in India to develop a state action plan, under the leadership of Mr Rajeev Sadanandan, former Additional Chief Secretary of Kerala. Mr Sadanandan also presides over our Hub’s National Advisory Group in India.

Apart from Kerala, only Madhya Pradesh and Delhi have action plans. Other states, including Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Gujarat, Karnataka, Puducherry, Meghalaya, Sikkim, Manipur, Haryana and Punjab, are working towards theirs.

AMR challenges

Participants at the event identified the following areas that must be a focus for addressing AMR at the state level in India:

Ownership was identified as critical for the successful development and implementation of any state action plan. States and districts may have distinct priorities depending on their food cultures, and action plans may need to be contextualised. Contextualisation should also ensure funding and the sustainability of any plan.

Multisectoral collaboration, and in particular inter-departmental collaboration and breaking down silos between government departments to bring them together through a high-level coordination committee, are important. The informal sector should also become a part of an ongoing dialogue, and farmers’ organisations, pharmacist organisations and public health workers should be included as they are close to the community.

Networks and decentralisation, including planning at the gram panchayat (local self-government) and district levels, are required given India’s size and diversity. Champions from every sector should be identified, and their work highlighted.

AMR awareness campaigns, a data dashboard and co-learning are necessary tools to mitigate AMR, a major challenge being the lack of availability of data from the community level. Both bottom-up and top-down approaches are needed. Best practices that evolve with time can be replicated in other settings.

Demystified language is needed to develop and implement AMR strategies. The language used for communicating AMR is loaded with biomedical terms, so the community and policymakers develop only a limited understanding of the gravity of the issue.

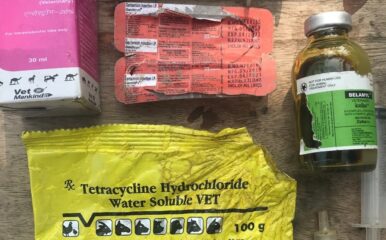

Poor antibiotic regulation, including over-the-counter medication and self-medication, need to be addressed. Pharmacists need to be sensitised about AMR.

AMR actions

Participants discussed the long- and short-term actions required to address AMR in India. Short-term actions included:

- Make the health care infection cost of AMR visible to policymakers.

- Ensure the language of AMR debates resonates with people’s needs.

- Establish an AMR call centre to provide help and share information.

- Provide farmers with easy access to vets as they mostly rely on pharmacists to buy medicines and seek health care for their animals.

- Seek funding from government departments and NGOs for training in infection prevention and control.

- Collect and analyse AMR data at one central point.

- Share feedback across departments.

- Provide farmers with incentives to use alternatives to antibiotics as growth promoters.

In the longer term, participants noted that the animal and food sectors should be brought together to implement AMR programmes, and human and animal health collaboration must be fostered. Celebrities could be made goodwill AMR ambassadors to build awareness.