Owning up: how can countries truly own efforts to tackle antimicrobial resistance?

Published on 09/03/2021

GBRC, India

As the World Health Organization’s Director-General, Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus noted in 2019, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is “one of the most urgent health threats of our time”. In fact, the burden of drug resistance is so high, it could overshadow the effects of COVID-19 in the next 30 years – by five times. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are set to be disproportionality affected by this public health crisis, which means governments in these countries must be fully equipped to own, respond to and combat growing drug resistance.

International support for activities to tackle AMR continues to emerge. And as the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness noted, country ownership is a critical determinant of aid sustainability. To indicate country ownership success, LMICs set about to draft their own operational development strategies with clear priorities.

But do plans and strategies truly allow countries to own development efforts?

This thinking has been carried through to AMR, where LMICs have drafted their own National AMR Action Plans outlining activities to combat drug resistance through surveillance, laboratory investment or drug regulation. Strategic plans are positive and can act as catalysts for action and provide much needed technical expertise in-country.

Furthermore, donors use these plans as blueprints for directing funding toward a country’s expressed priorities.

Political buy-in

However, these strategies are often developed with limited engagement of key national stakeholders and a limited attempt to build political will and buy-in for an AMR agenda. This is a critical issue, as political buy-in is essential in securing government funding and resourcing for implementation.

As a result, many governments have not yet taken concrete steps to implement national action plans in practice.

In addition, the strategic planning process is often led by the human health sector, with limited participation from the animal, environmental or food sectors. Because AMR requires a One Health response, when resources and funding are skewed toward human health surveillance or laboratory support the national government is unable to develop a true picture of drug resistance in the country.

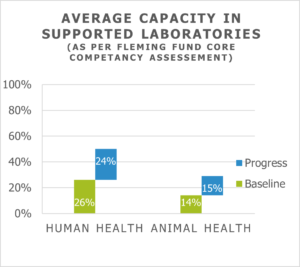

Baseline assessment data from the Fleming Fund, confirms that, on average, animal health laboratories have a much lower starting capacity (see graph) than human health laboratories. And, as noted, capacity building is slower in animal health laboratories, demonstrating that the human health sector often drives the AMR agenda.

Baseline assessment data from the Fleming Fund, confirms that, on average, animal health laboratories have a much lower starting capacity (see graph) than human health laboratories. And, as noted, capacity building is slower in animal health laboratories, demonstrating that the human health sector often drives the AMR agenda.

Competing crises: how can countries balance urgent vs important health crises?

Competing health priorities further challenge political buy-in for AMR – and nothing more so than COVID-19. Although many governments are more committed to boosting health spending due to the pandemic, future financing is likely to be allocated toward COVID-19 control measures rather than AMR.

In fact, observations in South Asia during 2020 show that laboratory resources were diverted away from bacteriology towards virology, there was less attention on antibiotic stewardship and many hospital AMR surveillance plans were suspended.

AMR needs a new narrative post-COVID-19 to spur countries to allocate resources and act on strategic priorities.

In addition, infectious and communicable diseases also distract from AMR investment. In South Asia, diseases like malaria or TB and health issues like maternal and reproductive health compete for pieces of the national health budget. Similarly, in animal health diseases like avian influenza or foot and mouth disease divert attention and resources away from AMR.

So where do we look for solutions?

National ownership is critical for tackling the global AMR threat. All actors have a role to play to ensure countries personalise and take hold of their nation’s AMR response.

External funders and donors can foster ownership by developing clear exit strategies and ensuring that action plans include accountability metrics like budget and resource commitments.

Realistic action

Rather than ending documents with a laundry list of aspirational ‘to dos’, plans should prioritise specific, realistic actions and implement incremental changes. Allowing extra time in the funding cycle for actors and governments to build buy-in is also crucial for reaping long-term rewards.

Non-governmental civil society can also encourage ownership by providing technical experts to fill government AMR committee roles and by sharing data and information with the public sector health system. For example, in some South Asian countries, the majority of AMR data is held in private sector laboratories. The private and public health sector could hold discussions to share evidence, surveillance data and policy ideas to foster an environment of wider collaboration.

For meaningful engagement, civil society should contribute evidence and actionable solutions, rather than only raising challenges.

Equitable representation

Finally, for equitable representation, government AMR agendas should sit at the supra-ministerial level, so that no single sector dominates the narrative or available funding. Government sponsored AMR committees could also introduce rotating heads or chairs so that each sector can lead national AMR discussions.

Policymakers should also find ways to mainstream AMR activities into existing human and animal health programmes to accommodate stretched budgets. For example, routine clinical lessons for health workers and doctors can be accompanied by messaging on antibiotic stewardship.

For effective AMR action, collaboration and cooperation between all AMR actors is essential and will help avert another global health crisis in the years to come.

Dr Vikas Aggarwal is South Asia Regional Lead, Fleming Fund Grants Programme, Mott MacDonald. He will be speaking in our next Roadmap Series event, Antimicrobial resistance governance: behaviour and blame, on Wednesday 17 March 2021.

This article represents the views of the author and not necessarily those of the Fleming Fund, Mott MacDonald or the UK Government.