From pushing alarm bells to informing policy: how the role of researchers is changing

Published on 30/10/2019

PxHere

Influenza epidemiologists and virologists were warning from as far back as the early 1990s that an avian or other influenza pandemic was likely. Their research revealed that the influenza virus’s impressive ability to evolve and skip the species boundary to humans made that gloomy forecast almost an inevitability.

It was soon after these warnings that Hong Kong saw the world’s first human case of highly pathogenic avian influenza. In 1997, a two-year-old child was confirmed to have contracted the virus. Eighteen human cases of this virus, H5N1, were recorded in all during this outbreak, six of which were fatal. The spread of the disease was only halted by slaughtering all chickens in the territory.

It was clear that the world needed to take appropriate action if the global pandemic and mass loss of life that the World Health Organization (WHO) now warned of was to be avoided. Countries were advised by WHO to get together a pandemic preparedness plan, complete with specific tasks to accomplish.

Most of the countries in the developed world went on to prepare their national avian and pandemic influenza preparedness plan following WHO and UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) guidelines. In many low- and medium-income countries though, the path to a preparedness plan was not so smooth. In Bangladesh, we had little or no experiences with avian influenza at that time. We did not even have a human seasonal influenza surveillance platform in the country.

Pandemic preparedness plan

With the support of WHO and FAO however, in 2004 Bangladesh did start work on developing its plan. Bangladesh’s Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR) was given responsibility for coordinating the activities with the Department of Livestock Services and the country’s first National Avian Influenza and Human Pandemic Influenza Preparedness and Response Plan 2006-2008 was approved by the Honourable Prime Minister of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh on 17 April 2006.

Prepared by a National Multi-sectoral Planning Team, the plan received inputs from the Ministry of Environment and Forest, Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock, and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. It was the first time the animal and human health ministries had formally collaborated in Bangladesh. The guidelines in this first plan were key in helping the country manage more than 500 outbreaks of avian influenza in poultry, as well as three outbreaks in humans.

It was as a second plan was pending final approval, in June 2009, that the H1N1 (‘swine flu’) pandemic struck the world. Within a few months, almost all countries, , including Bangladesh, were affected. More than 280,000 people have been estimated to have died of the disease worldwide, demonstrating the truth behind the warnings of more than a decade earlier.

With multiple zoonotic influenza viral strains circulating in domestic animal populations in several countries, including Bangladesh, the threat of another pandemic influenza is ever knocking and so work to strengthen preparedness and response plans in Bangladesh is an ongoing one.

The country’s challenge for its third plan, now finalised, was not only to prepare the country to face any pandemic of a novel influenza virus, but also to prevent such an emergence by reducing the viral transmission in the domestic animal reservoir, and the exposure of people to those viruses. Work on it has benefited from reviewing the national and global experiences of the 2009 pandemic and considering the achievements and challenges faced during implementation of the first two plans.

One Health

The third plan provides a strategic framework for coordinating activities both within and between different sectors and stakeholders for preparedness and response to avian and pandemic influenza. With its first and second plans, Bangladesh had shown success in practising a One Health approach and this has been recognised with the creation of a three-tier coordination mechanism: an inter-ministerial One Health Steering Committee, a National One Health Advisory Committee and a One Health Secretariat to facilitate the development of One Health zoonotic disease control policies. By formally involving all the relevant governmental ministries and organisations, this secretariat is becoming an essential tool to promote good communication and to coordinate activities across the agricultural, animal health, human health and environmental sectors.

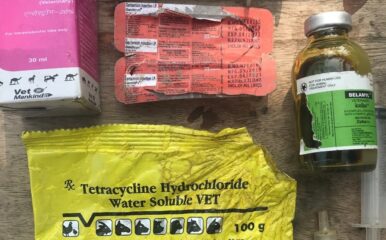

Additionally, this third plan is benefiting from a number of revisions to its Prevention and Control component as new research informs policy for preparedness and response. For example, the plan will promote the adoption of national biosecurity standard operating procedures (SOPs) by increasing farmers’ access to economic information and reliable credit systems.

Biosecurity and farmer access to credit may not immediately appear related but recent anthropological and social science studies have demonstrated that socioeconomic barriers and a lack of economic independence mitigate against behaviour change to improve biosecurity. In short, improved biosecurity, which is essential for avian influenza prevention and control, won’t happen unless farmers’ economic independence is addressed.

The plan also aims to reduce the number of intermediaries involved in the trade and marketing of poultry from farms to markets – that is, the number of people whose hands a bird goes through as it moves from farmer to final consumer.

Again, it is research (some yet to be published) into the Bangladesh poultry production and distribution networks that lies behind this revision. Research has demonstrated that multiplication of intermediaries, first, creates opportunities for the mixing of poultry of different origins and their associated viral strains, and, secondly, results in the amplification of the viral circulation, as poultry spend a longer period of time with traders.

Other revisions in this new plan include the move towards a ‘one vehicle, one farm, one market’ model, in which the mixing of several poultry species and breeds within the same vehicle and the movements of traders between multiple markets, is avoided. The justification for this is to reduce the risk of mixing different viral strains circulating in different geographical areas and farming systems, and to reduce the risk of contamination of markets through the movements of mobile traders who have been found to trade poultry in multiple locations in the same city.

Similarly, the plan allows for improving the safety of live bird markets and wet markets by avoiding the mixing of several poultry species and breeds on the same stall. This again is to reduce the risk of mixing different viral strains circulating in different farming systems.

Improved policy framework

Some of the research that fed into this new, improved policy framework was undertaken under the Behavioural Adaptations in Live Poultry Trading and Farming Systems and Zoonoses Control in Bangladesh (BALZAC) project. This research will be continued and built upon in the One Health Poultry Hub.

As our knowledge increases of how avian influenza viruses circulate, evolve, amplify and transmit, taking many different kinds of data into account, obtained through One Health – or interdisciplinary – research, is essential to ensure policy can be better informed. It will lead to better outcomes and better impact all round.

The role of researchers should not be limited to that of pressing pandemic alarm bells, as those epidemiologists and virologists did back in the early 1990s. Much better that we are coming up with relevant results and feeding into policy processes to ensure we are suitably prepared. In this, Bangladesh is showing the way.