Barriers to addressing the malnutrition crisis in India

Published on 10/06/2021

People from marginalised communities struggle when it comes to the social determinants of health – those non-medical factors that influence people’s health such as access to safe water, sanitation, education, livelihood opportunities, shelter, housing, safety, public transport and good nutrition.

Many from marginalised communities do not get minimum wages and work in exploitative conditions with very little recourse to judicial or legal support. These circumstances, which have been aggravated by the unplanned massive COVID-19 lockdown, affect all aspects of their health.

Diseases and malnutrition

It is expected that there will be a surge in vaccine preventable diseases, communicable and non-communicable diseases, as well as malnutrition related issues. Apart from a rise in stunting and undernutrition, manifestation of individual diseases like marasmus (a severe form of malnutrition), vitamin A deficiency, rickets and more are expected to manifest over the next few months.

The 2019 National Family Health Survey shows some alarming statistics on nutrition which will definitely have an adverse outcome on the population, especially the poor and vulnerable. For example, just 12.8% of children aged 6-23 months receive an adequate diet, stunting in under-fives is at 35.4% and underweight in under-fives at 32.9%. Women with a body mass index below normal (<18%) constitute 17.2% of all women, while the figure for men is 14.3%. Overweight or obesity (BMI >25) in women and men is at approximately 30%. Anaemia (haemogloblin levels below 11g/dl) in children aged 6-59 months is 65.5% of this group, while anaemia in non-pregnant women aged 15-49 years (<12 gm/dl) is 47.8%.

Vegetarian India?

Although India has been traditionally promoted as a ‘vegetarian’ country, in reality the country has a rich meat-eating culture with different meats eaten in different forms and preparations. The Dalit communities (communities traditionally oppressed under the caste system) mostly eat organ meat and have developed good systems of meat preservation practices. However, most of these systems have not been modernised because of the caste system’s aversion to meat.

In India, about 20% of the population identify as vegetarian and claim to eat no animal-source foods. However, in reality, they consume animal-source foods like milk and other dairy products while abstaining from eggs, poultry, fish and other meats. Natarajan and Jacob point out that ‘self-identification’ into the categories of vegetarian and non-vegetarian is not reliable because even meat-eating people may self-identify as vegetarian out of social pressure.

The cost of dairy usually makes it unaffordable for poorer communities who would rather invest in cheaper sources of meat like beef and organ meat. However, meat eating and meat eaters have been viewed as ‘unclean’ or ‘polluted’ and this has led to criminalisation and targeting of these communities.

A vegan agenda

Researchers have at times had their work on this topic wrongly interpreted. In one recent example, a collaborative study from the International Food Policy Research Institute, Family Health International and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the results were initially promoted on social media with the very damaging statement “vegetarian women are more likely to have probability of nutrient adequacy and diet diversity during pregnancy than non-vegetarian women”. Although this was later corrected, these statements tend to chime well with increasing vegan sentiments promoted from some quarters in the West.

In regards to the statement above, it should be noted that, firstly, ‘vegetarian’, and ‘non-vegetarian’ are not scientific categories. Secondly, women from better socioeconomic backgrounds are likely to enjoy a more diverse diet with more access to animal foods like dairy. Women from dominant castes are also likely to be from a better socioeconomic background, which in turn can contribute to better pregnancy outcomes.

At times it can seem that a growing global agenda of pushing plant-based foods is having the effect of bolstering casteist forces that want to keep a majority of the Indian population hungry and undernourished.

Further, the predominance of vegetarians in policymaking in India leads to an undue focus on cereals and millets as a source of food, to the exclusion almost completely of animal-source foods. This has resulted in the kind of nutritional crisis that the country is now in.

Climate change

It is always good to provide foods that are region specific, culturally relevant and produced locally. This has multiple benefits, including on climate change. India has 34 million pastoralists managing a livestock population of more than 50 million, contributing to the production of milk, meat, leather, wool and animals for traction and manure.

Pastoralists in India are often from oppressed communities and have very little bargaining power or rights to land for grazing. They contribute to increasing the fertility of the land and increase local food sovereignty making the community more self-sufficient. Each geographic area maintains its diversity rather than having homogeneous, manufactured goods shipped or flown and contributing to air miles, from other regions. However, that does not suit the industrial model.

It is important that one homogeneous food is not promoted and diversity in foods is encouraged. Also, the focus should be on natural foods that do not have an ‘ingredient list’.

In India there are strict legal provisions preventing the entry of corporates into the provision of foods to pre-school children. This is a good policy and should be strengthened and extended to all children.

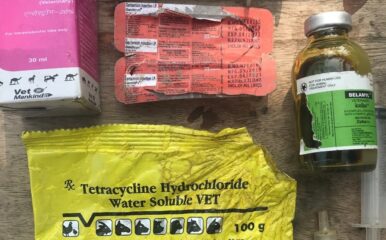

However, there is a tendency to address malnutrition with supplements, fortification, packaged and processed foods. Having a balanced diet with foods from multiple food groups would be a better way forward.

People should demand that the government invest more in technology to improve the efficiency as well as methods of preserving, transporting and supplying animal-source foods, keeping in mind animal welfare.

There is very little representation of vulnerable communities at policymaking levels in India. Corporates, multinationals and caste groups collude to make decisions which are mostly exploitative or extractive of natural resources and human labour and do not benefit ordinary people. These decisions are not transparent or accountable, often made behind closed doors. We see the devastating impact of this in decisions around natural resources, education, livelihood, nutrition, healthcare.

Foregrounding of community choices, local traditional and cultural foods often coincides with sound nutrition science. It is the unethical corporates and intermediaries in the food system that adversely affect people’s access and choice of food. People and communities need to reclaim their traditional home-grown foods. for they positively impact on climate and nutrition.

Dr Sylvia Karpagam is a public health doctor and researcher based in South India and part of the Right to Food and Right to Health campaigns. She blogs at: drsylviakarpagam.wordpress.com