Anatomy of two COVID-19 cluster events in India

Published on 30/03/2020

Trinity Care Foundation/Flickr CC BY 2.0

India has been applauded for its quick action to quarantine people and shut borders in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Relative to its population size, the rate of infection remains low in India.

In an extreme step to curtail the spread of COVID-19, the Government of India issued its first advisory on 3rd March to suspend visas granted to the nationals of China, Italy, Iran, South Korea, and Japan. It also became mandatory for all foreigners and Indians travelling directly or indirectly from China, South Korea, Japan, Iran, Italy, Hong Kong, Macau, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Nepal, Thailand, Singapore and Taiwan to undergo medical screening at the port of entry. On 4th March, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare made it mandatory for all international travellers coming to India to undergo screening and 14 days voluntary home quarantining, even in the absence of any symptom. Poor compliance by Indian travellers and limited tracing of travel history have seemingly posed grave challenges in preventing community transmission.

This is the story of two cluster events in India, in the states of Rajasthan and Kerala. Rajasthan is the seventh most populous state in the country, and Kerala 13th. In terms of COVID-19 cases, their ranks are 6th and 2nd (28th March, 2020) respectively.

Bhilwara – spread from an ICU case

Bhilwara, a town in Southeast Rajasthan with a population about 400,000, is famous as a textile hub. It has rapidly emerged as a COVID-19 hotspot with 21 positive cases, 15 detected from a single hospital on the last count, and two deaths. 588 samples have been sent so far of which 485 have been negative. Even though the first case of COVID-19 in Rajasthan was detected on 12th March, the virus seems to have entered Bhilwara long before that. How did the virus enter the city?

It began when a private hospital (Brijesh Bangar Memorial Hospital) examined a case of pneumonia without enquiring about the patient’s travel history. The patient was kept in an intensive care unit (ICU) with six other patients and was referred to Jaipur hospital when their health condition failed to improve much. The news of this patient’s death came on 13th March. A few days later, the doctor who had examined this patient was kept in isolation along with some other staff of the same hospital and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (the virus behind COVID-19). However, before being tested positive, the doctor reportedly came in contact with over 6,000 cases from 13 districts and four neighbouring states.

The whole city was gripped by a fear of impending doom with the news of the doctor’s infection. The lack of credible information on early transmission added fuel to the fire. Rural-urban migration is high with the textile factories in the area; an estimated 40% of rural households have migrant populations. The mining areas in the district attract migrants from other districts of the state. With Bhilwara certainly emerging as a COVID-19 cluster, community transmission is almost a certainty though there is no official confirmation of it.

The district officials took a series of steps to limit the transmission. The local Singoli Mela (festival) scheduled to begin on 23rd March was cancelled. Awareness campaigns were organised and homeopathic medicines were distributed to approximately 1,000 people near Bada Mandir. Nearly 78,000 houses were surveyed, covering a population of about 350,000. More than 5,000 people are currently in isolation in their homes, and 2,500 with flu-like symptoms are under surveillance. Funeral and death related rituals have now been curtailed.

A nationwide lockdown was announced on 24th March but Bhilwara was in lockdown four days prior to that and the lockdown seems to be working in controlling the cluster outbreak. Apart from government officials, various non-governmental organisations (NGOs), social work organisations and donors, including industrialists and textile mill owners, have contributed to the success of the ongoing lockdown.

The Health Minister has assured that there is no shortage of masks, sanitisers or ventilators. Private hospitals also created isolation wards for the treatment of suspected cases of COVID-19. Anticipating a surge in cases of about 6,000, five private hospitals, guest houses and resorts are being acquired by the state government. Even in the backdrop of this event of clustering, Panchayat (local self-government) elections in Mandal Block still took place (84.6% cast their votes) and people kept visiting the hospitals for minor ailments.

The Chief Minister of Rajasthan met political and religious leaders of the state on 18th March and religious leaders responded by appealing to devotees to avoid visiting religious places and festivals. Despite that, people continued to participate in religious gatherings, sometimes with masks.

Kasargod – a traveller’s tale

Kasaragod District in Kerala had a similar experience with the district under a complete lockdown since 21st March.

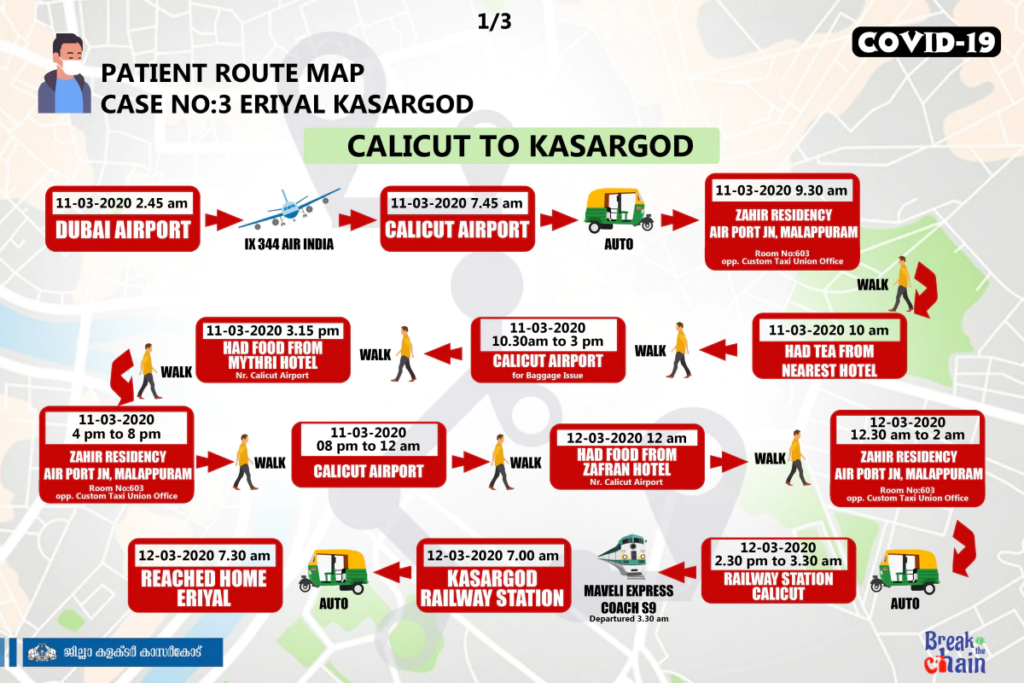

It started when a SARS-CoV-2 infected patient arrived at Kozhikode from Dubai on 11th March. He stayed in a lodge and travelled by sleeper bus. He travelled to several locations in Kasargod for five days, during which time he met several people, including the local members of the Legislative Assembly (elected state assembly representatives). He tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on 16th March and was suspected to have potentially infected over 3,000 people as he had used public transport and attended some mass gatherings.

The local administration is struggling to trace the people he contacted and might have infected while the number of cases in the district is on the rise. The state health administration issued these route maps for contact tracing.

This happened despite all passengers with a foreign travel history being advised to be on home quarantine for 14 days. Interestingly, the Union Cabinet Secretary, Rajiv Gauba, leading the COVID-19 crisis management group, wrote a letter to states pointing to the “gap between the actual monitoring for COVID-19 and the total arrivals” from abroad. With an estimated 1.5 million travellers arriving in India over the past two months, the Centre urged states and Union Territories to involve district authorities in improving tracking.

Hotspot detection

The World Health Organization (WHO) designed the Risk Communication and Community Engagement (RCCE) Action Plan Guidance COVID-19 Preparedness and Response tool to support risk communication, community engagement staff and responders working with national health authorities, and other partners to develop, implement and monitor an effective action plan for communicating effectively with the public, engaging with communities, local partners and other stakeholders to help prepare and protect individuals’, families’ and the public’s health during early response to COVID-19. The adaptation and the application of this tool seems to have been lacking in these hotspot contexts.

Hotspot detection is a spatial clustering process to detect spatial areas on which specific events thicken, with the patterns geo-referenced as points on the map. The features are the geographical coordinates (latitude and longitude) of any event.

Hotspot detection is particularly critical in outbreak investigations for studying localisation and foci of diseases. The geometrical shapes of hotspot areas algorithms based on density are used to measure the spatial distribution of patterns on the area of study, and these algorithms have a high computational complexity.

Pung et al have done an excellent analysis of three cluster events in Singapore involving a Chinese tour group, company conference, and a church to demonstrate the transmissibility of COVID-19 in community settings beyond household clusters.

States in India with high travel volumes from abroad need to enhance surveillance systems to identify locally acquired cases with active case-finding among close contacts of cases, and institute containment efforts to prevent widespread community transmission.